Pointing Webhooks to a Local Container with ngrok

This was a fun bit of development work with a couple of gotcha’s, so I thought I’d write it up into a blog post in case anyone is trying to do the same thing.

The Problem

We’ve been building a number of customisations for ContentStack CMS, and as with many SaaS integrations, it uses webhooks to allow us to run custom code in response to certain events that occur within ContentStack itself. We have an API hosted in GCP Cloud Run that exposes endpoints for this very purpose.

As the webhook needs a public URL in order for ContentStack to send the request to it, we can’t trigger the code when it’s running in our local development environment, which is a Docker container. Every engineer has their own personal development stack which is created and updated by running our schema generation code locally. So ideally, webhooks triggered from the development stack would send the request to the locally-running, development version of the API.

The Idea

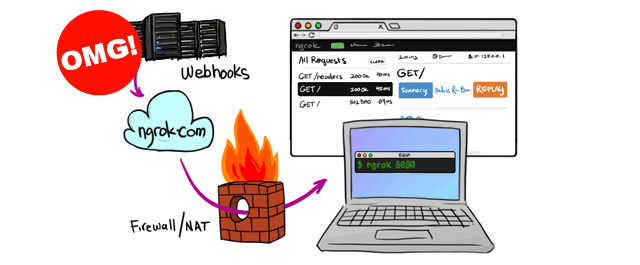

Ngrok is a well known utility for exposing local endpoints with a public URL, so we thought we’d have a look into whether we could use that to point webhooks from the feature branch stack to the locally-running API container. Ideally, that should be without having to do any manual configuration.

The Solution

When running the API locally (using docker-compose), it will launch a side-car container running ngrok that will create a public URL for the exposed port of the API container.

Then, when generating the schema for the development stack, it would query the local ngrok container to get the public URL, and set that as the webhook URL for all webhooks. As a result, any events that occur within the dev stack in ContentStack will be sent to the locally-running API container.

Creating the Ngrok container

Previously, as it was a single container, the API was just run using a single docker run command, which in turn was run using a make command. The docker run command was already getting unwieldly due to the volumes, port mapping and environment variables, and now there was to be a 2nd container, it made sense to re-factor into a docker-compose file. Here’s the contents of the file:

version: "3.9"

services:

api:

build: .

entrypoint: npm run dev

volumes:

- ./:/usr/app

- ~/.google_cloud/pollen_qa_credentials.json:/secrets/google/credentials.json

ports:

- 3000:8080

environment:

- ENVIRONMENT=dev

- CONTENTSTACK_EMAIL=${CONTENTSTACK_DEVOPS_EMAIL}

- CONTENTSTACK_PASSWORD=${CONTENTSTACK_DEVOPS_PASSWORD}

- API_KEY=${POLLEN_API_KEY}

networks:

- pollen-api

ngrok:

image: wernight/ngrok:latest

entrypoint: ngrok http api:8080

ports:

- 4040:4040

networks:

- pollen-api

networks:

pollen-api:

The docker-compose file creates a shared network that both containers use. The ngrok container runs the ngrok http api:8080 command, which tells ngrok to create a public URL and forwards all requests to that address (port 8080 on the api container).

Pointing the Dev Stack Webhooks to the Ngrok URL

To do this, when we generate the dev stack schema, we need to query the ngrok URL from the ngrok container and set the result to an environment variable. This is then passed in as part of the docker run command. Here’s the shell command for doing that:

curl -s $(docker port api_ngrok_1 4040 | grep 0.0.0.0)/api/tunnels | jq -r '.tunnels[].public_url | select(test("https.*"))')

We’ll need to break this down into parts. First, there’s this bit:

docker port api_ngrok_1 4040 | grep 0.0.0.0

This uses the docker port command to get the URL of the running ngrok container. We then pipe it into a grep that filters the results for the URL that’s on 0.0.0.0, as it can return multiple results, which would break the sub-command.

We then use curl -s to silently send a request to ngrok’s api/tunnels endpoint, which returns a JSON object containing all the endpoint data. The JSON object looks something like this:

{

"tunnels": [

{

"name": "command_line (http)",

"uri": "/api/tunnels/command_line%20%28http%29",

"public_url": "http://00bbdd913fc3.ngrok.io",

"proto": "http",

"config": {

"addr": "http://api:8080",

"inspect": true

},

"metrics": {

"conns": {

"count": 0,

"gauge": 0,

"rate1": 0,

"rate5": 0,

"rate15": 0,

"p50": 0,

"p90": 0,

"p95": 0,

"p99": 0

},

"http": {

"count": 0,

"rate1": 0,

"rate5": 0,

"rate15": 0,

"p50": 0,

"p90": 0,

"p95": 0,

"p99": 0

}

}

},

{

"name": "command_line",

"uri": "/api/tunnels/command_line",

"public_url": "https://00bbdd913fc3.ngrok.io",

"proto": "https",

"config": {

"addr": "http://api:8080",

"inspect": true

},

"metrics": {

"conns": {

"count": 0,

"gauge": 0,

"rate1": 0,

"rate5": 0,

"rate15": 0,

"p50": 0,

"p90": 0,

"p95": 0,

"p99": 0

},

"http": {

"count": 0,

"rate1": 0,

"rate5": 0,

"rate15": 0,

"p50": 0,

"p90": 0,

"p95": 0,

"p99": 0

}

}

}

],

"uri": "/api/tunnels"

}

So what we need is the public_url property from the https endpoint. In order to get this, we pipe the JSON result into the incredibly useful jq command-line utility. That’s what this bit does:

jq -r '.tunnels[].public_url | select(test("https.*"))')

The -r command gives us the raw JSON output. We then use the query syntax to select the public_url property of every object in the tunnels array. This gives us both the http and the https public_url values. We therefore need to pipe the result of that into the select function, which allows us to specify a test that will resolve to true or false. The select function will only return results where the function it’s supplied resolves to true. The test function allows us to pass in a regex which will only match strings that start with https.

The Result

After a bit of trial-and-error, the above worked perfectly. We’re just using the free version of ngrok, which comes with a number of limitations, including that the tunnel will only stay open for a few hours, so if it’s a long piece of development work, we need to re-run the schema generation every now and again. It only takes a minute or so, so it’s not the end of the world, but if it becomes problematic we can get a paid ngrok subscription. That would also simplify the above as we could get fixed URL’s for each engineer. But then where’s the fun in that?